Donnie

D’Amato

donnie.damato.design Founder, Chief Architect

Design Systems House (ds.house)

The following is a recap of a year long research and development journey revealing a method to take semantic responsibility away from design tokens. I will attempt to demonstrate how we might execute design decisions not through complex token naming exercises, but by burdening rectangles with glorious purpose.

design systems are for people Jina Anne

A year ago, at the time of this writing, my wife and I were invited to attend Schema 2022, Figma's design systems conference in New York. There were a collection of several great talks throughout the day. One of these talks was by Lauren LoPrete, who walks the audience down her path of growing influence with her teams. Her talk echoes a common statement within our practice; “design systems are for people” which I wholeheartedly agree with. All of the tokens and components we spend time with everyday will mean little without adoption. So building trustworthy relationships is key to success in our practice.

The final slide of Lauren's talk ends with the following sentence: “They're just rectangles on the internet.”

There's a collective chuckle from the crowd, myself included. It's common for folks to joke about the work we do.

However, in retrospect, I wouldn't have been in that room without rectangles. My career, which puts a roof over my head and food on the table, would have been completely different without rectangles. I wouldn't have met my wife without them. The work that we do with rectangles is truly changing humanity every day. In reality, rectangles make the world go round, socio-economically speaking. I didn't know it then but I was about to discover that these rectangles could also be a looking glass to a whole new design paradigm.

In order to understand how I came to this conclusion, I'll walk you through my thought process as I ask questions that challenge our current norms with surprising results.

🤔

Do new expressions need new tokens? Question 1

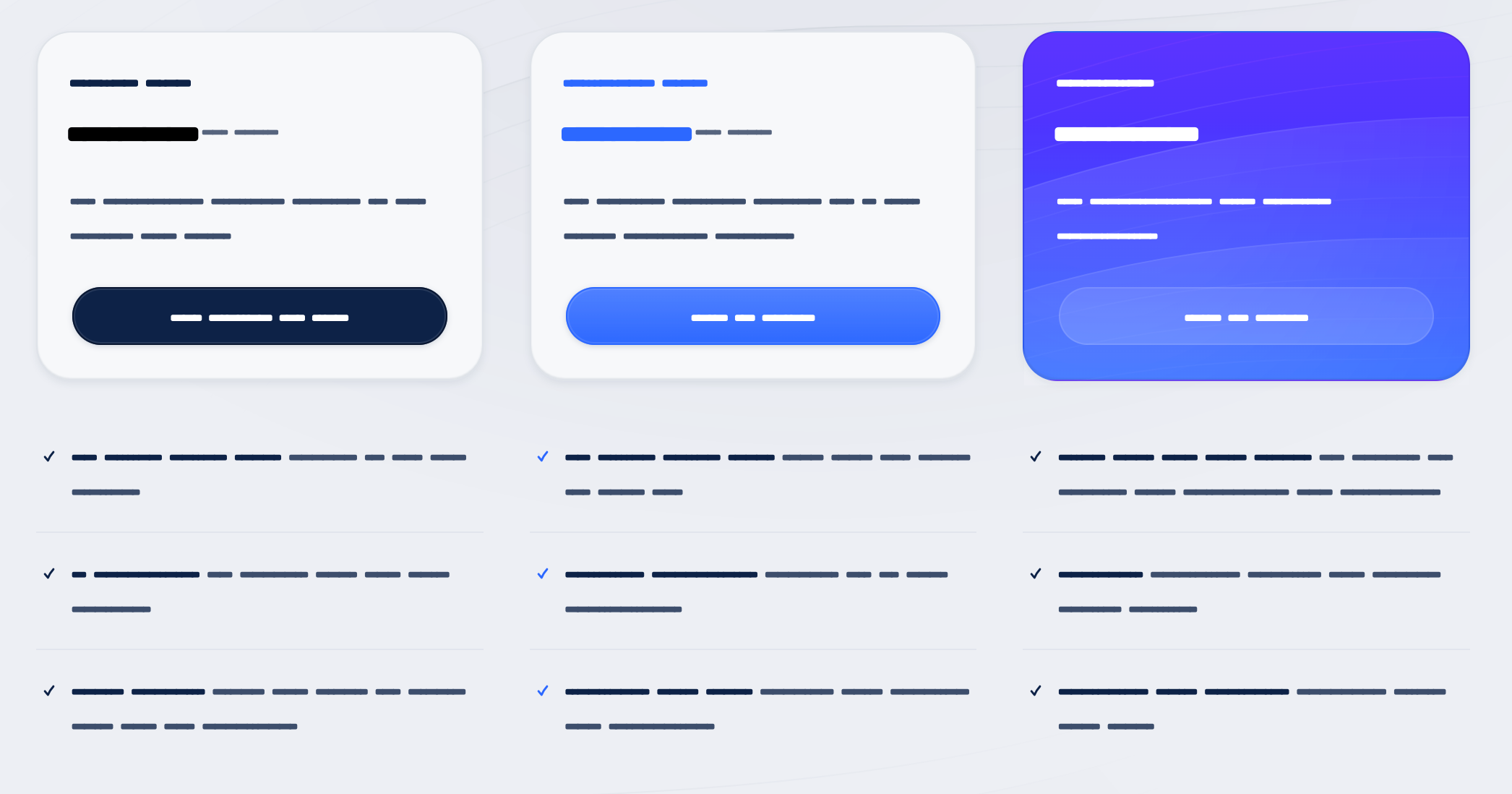

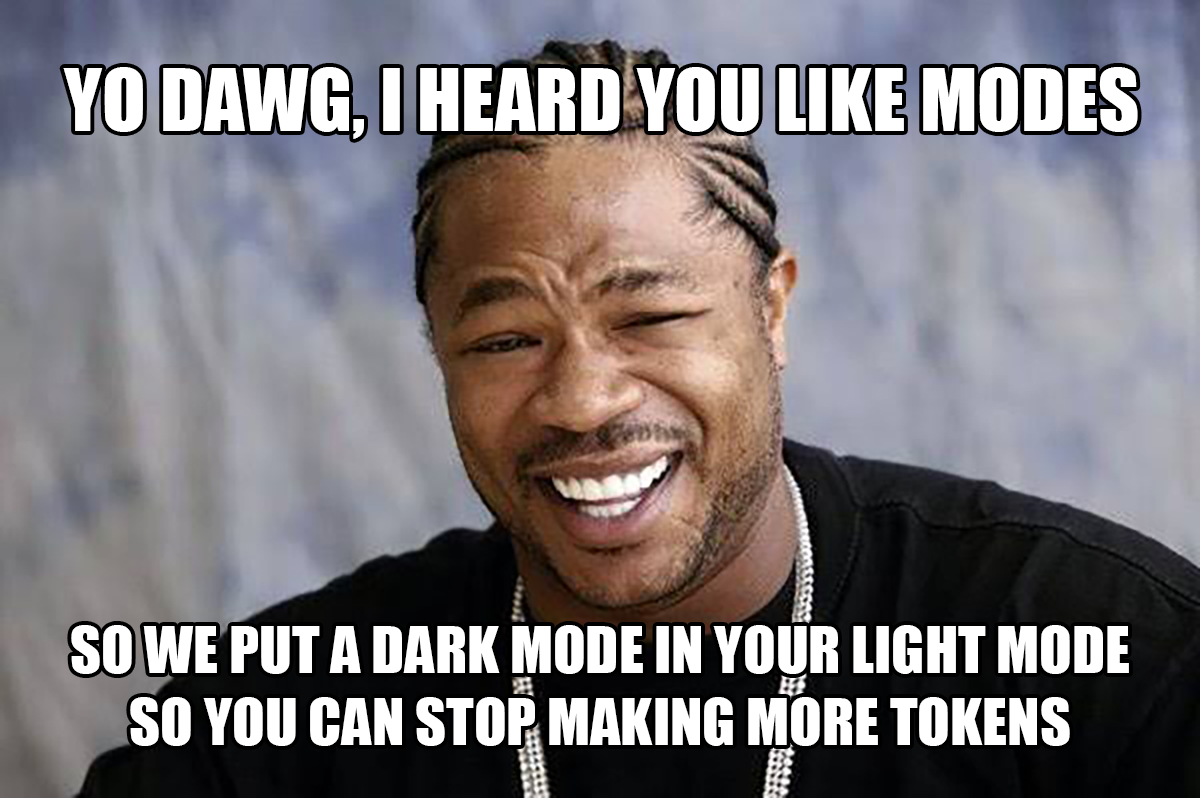

In this example, we have a section of a pricing page. Each card has some text, a button, and maybe some links. The task would be, how do we support these slight variations using design tokens?

What many folks might do is create tokens that describe the concept of inverse, highlight, or accent to support the difference between each of the cards and the rest of the page. Maybe text accent, or button background accent, et cetera. After all it is just a small part of the larger experiences. What harm could be done?

What should happen if we need to add a text input within these cards? Maybe that input has an error that needs to be displayed? How do you account for these additions?

If your answer is more tokens, you're going to find that you'll end up trying to have an accent variation of every semantic token you have. You'll have to cover every possibility of each element appearing in this accented area of the page; at least doubling your token set; or in this case tripling.

I don't know about you, but I'm trying to maintain fewer tokens, not more.

new tokens

What I recommend is to instead consider each card as a separate mini-region which creates a scope of new values. There's a few benefits to this, one of which is no new tokens. The button background continues to use the button background token just with a new value applied in the same way that you might apply new values for dark mode.

In this way, each card is a boundary for new values for the same elements and tokens. It's functionally the same text, button, and links just visually changed by existing within a new scope all co-existing on the same page.

Keep this idea, put it in your pocket, and let's save it for later.

How might we make space semantic? Question 2

At this time, I'd like to focus on how we might expand other themable properties into semantic naming. Is semantic naming for border radius possible? Spoiler, no it's not, but what about spacing?

Spacing tokens in many design systems are either published as T-shirt sizing or proportional amounts, neither of which are semantic; the names of these tokens give no indication about where to use them.

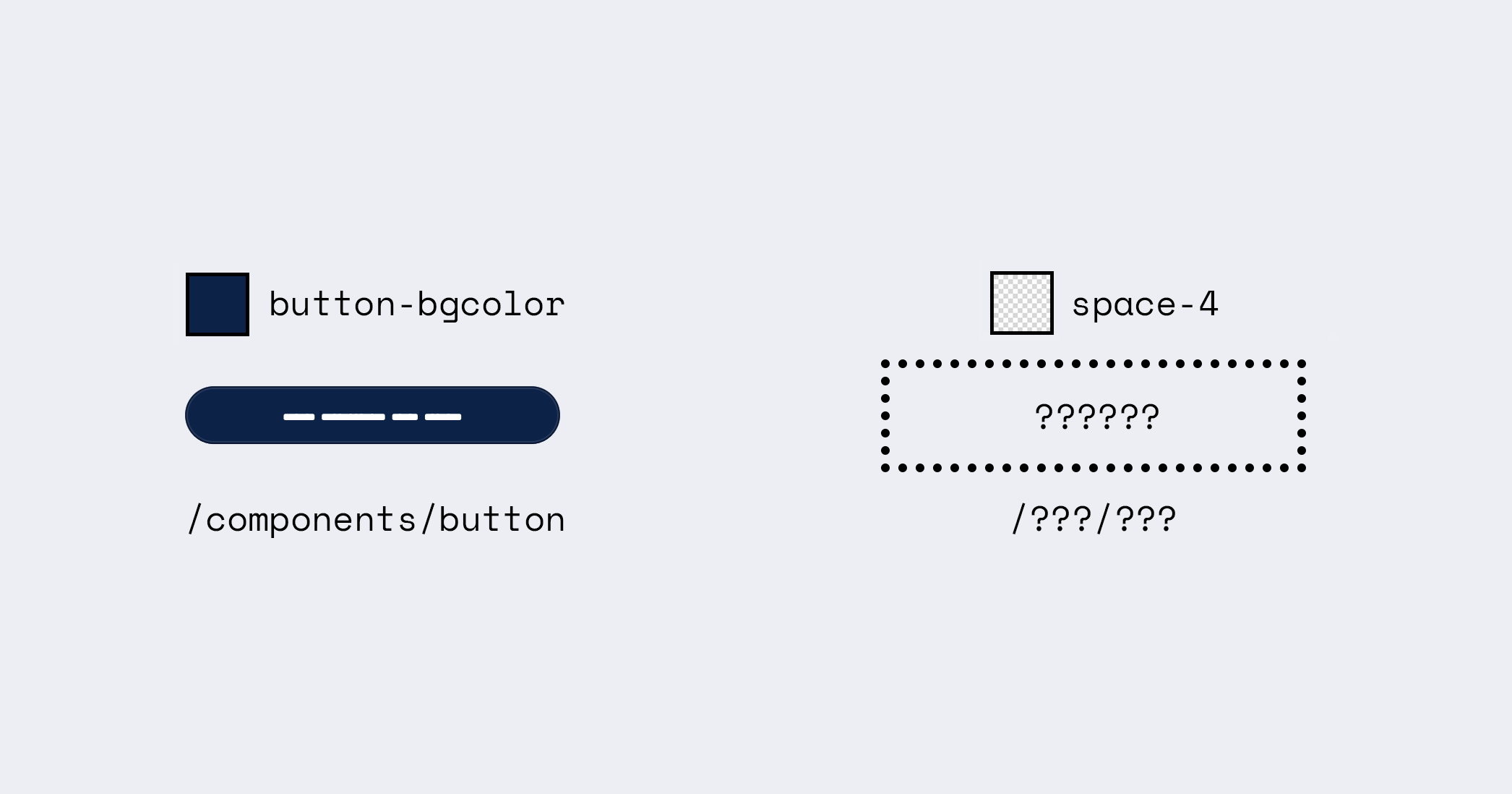

Think about if a person was asked to markup an interface with only a list of token names. It is logical that the semantic token name button-bgcolor is meant to color button backgrounds. While the proportional scale token space-4 gives no indication where it should be applied using only the token name. This means that they should be segregated into different categories, where button-bgcolor is semantic and space-4 is not.

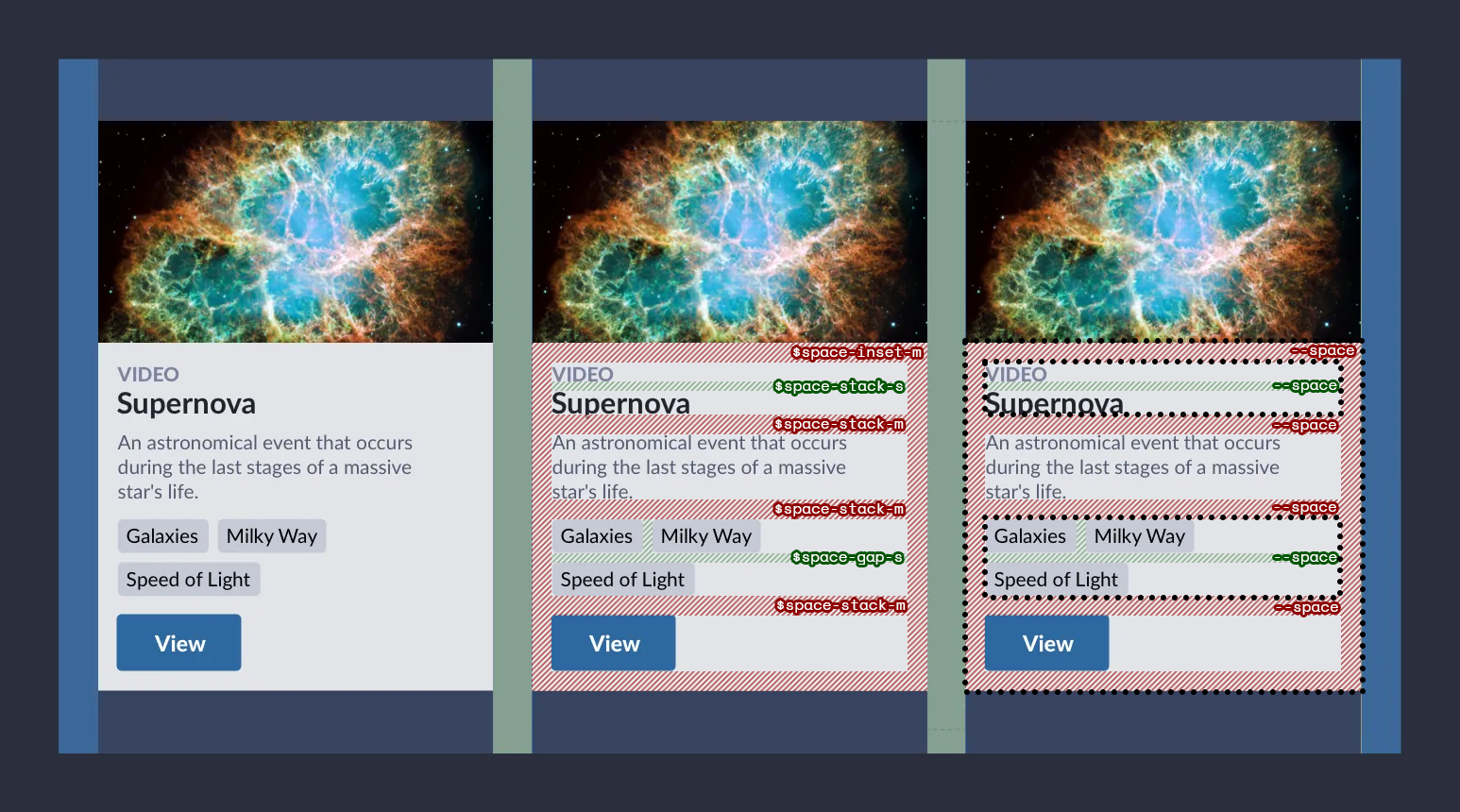

It was important to me that whatever the solution of this exploration, that it achieved the same visual results in comparison to existing best practices, even if executed differently. I was heavily influenced by Nathan Curtis's article about space throughout this work as his outlook has been adopted by community several times over.

The result of that research was called Complementary Space. A technique that suggests we can mark an area with a single token that means “space goes here” and then a designer determines how much space in a new way; using regions.

Each region determines what the value of space is within. You can create different amounts of space by assigning a different value for the tokens in that region.

In this way, we no longer need to have space token naming at all! If the regions are the scale, and each region goes down one level of space, you can go down multiple levels by continuing to nest regions. Only going in a decreasing direction is appropriate because as we traverse deeper into an interface, there is less room and compositions are naturally more compact.

What are the shared principles in these approaches? Bonus Question

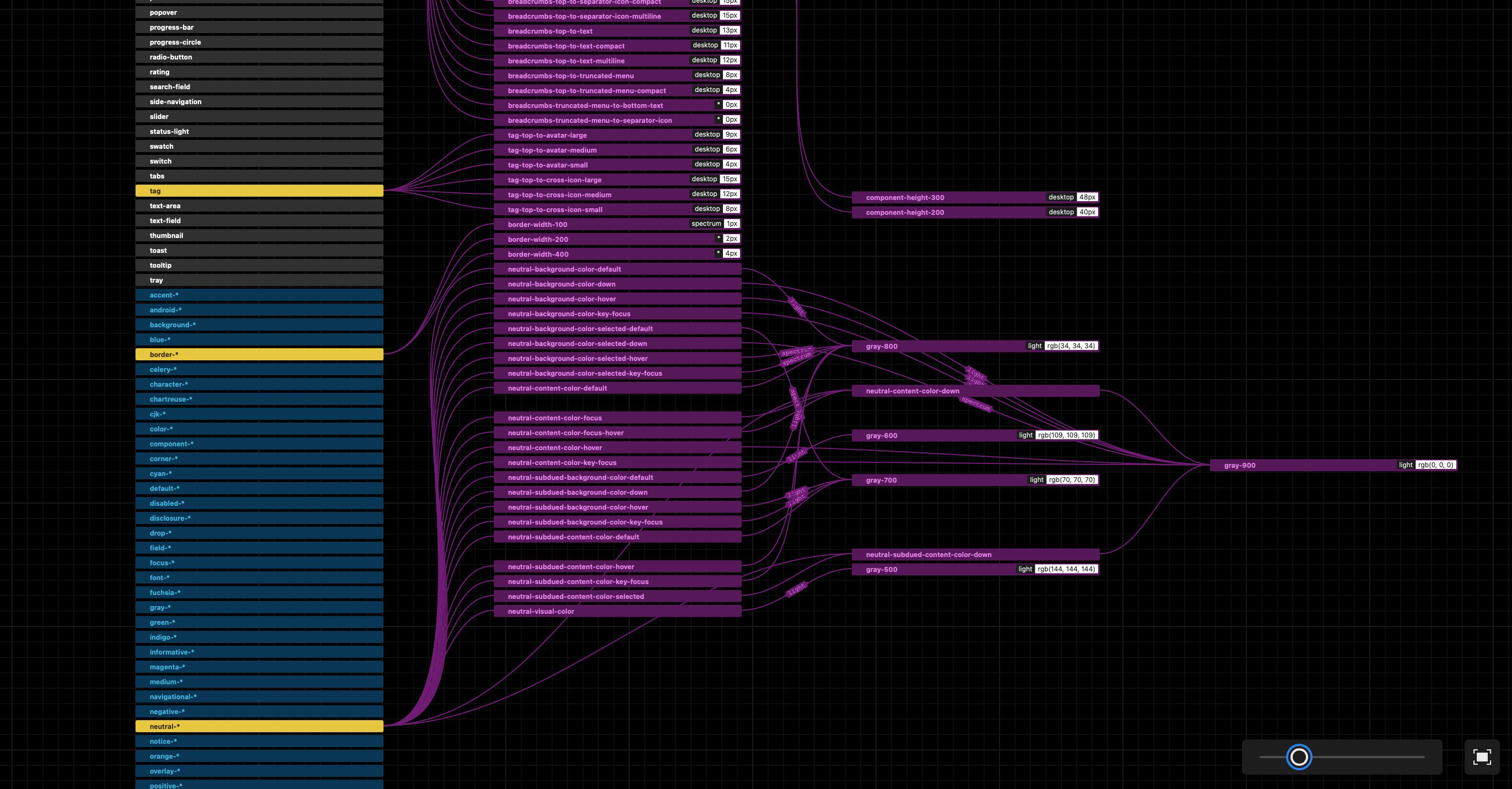

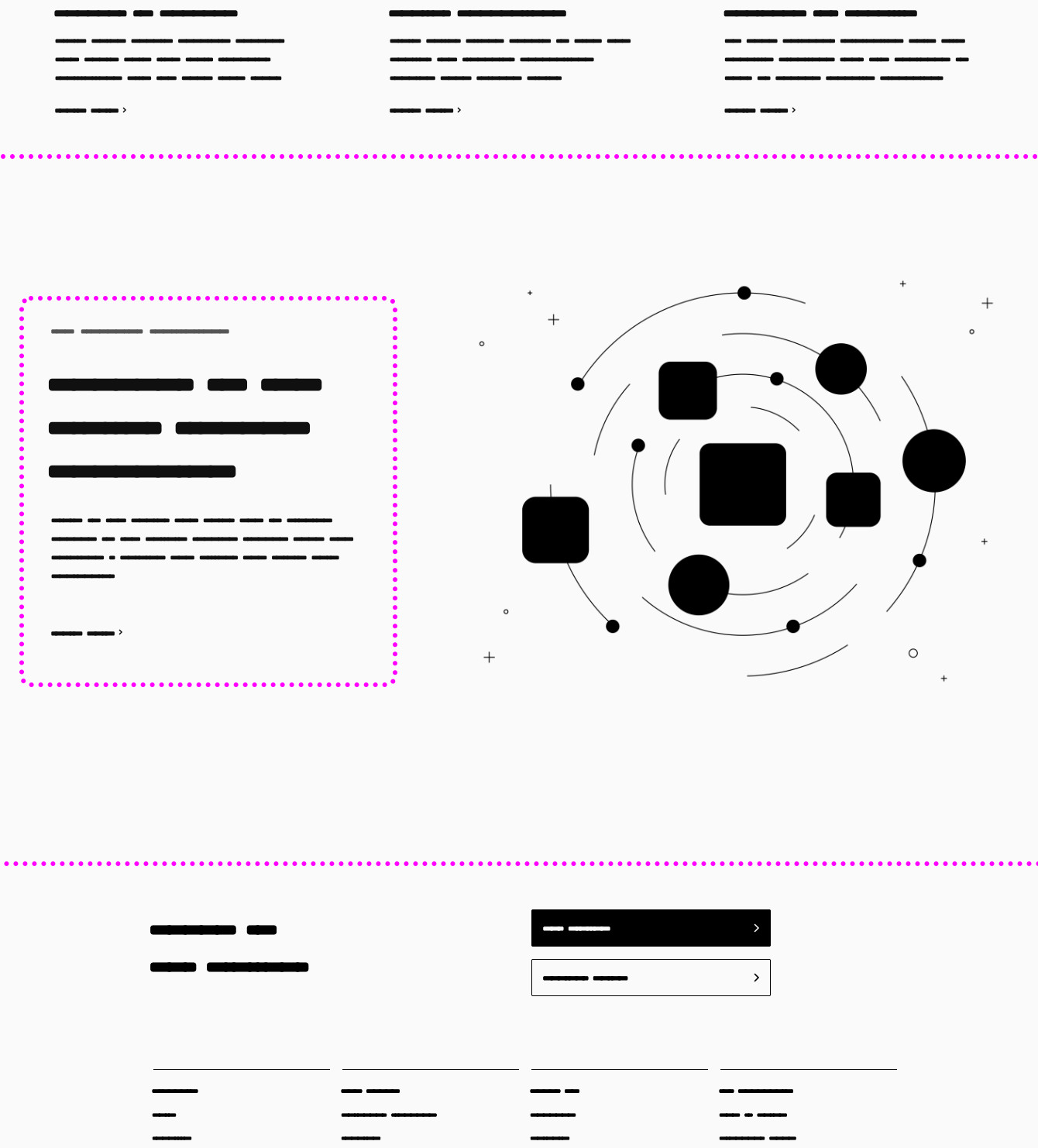

Through these separate units of work I soon realized that both questions resulted in using the same technique of changing token values depending on a targeted scope. From here, I wanted to understand the fundamental principles I was uncovering so that it was clear when tokens were meant to drive design decisions and when scope should be considered instead.

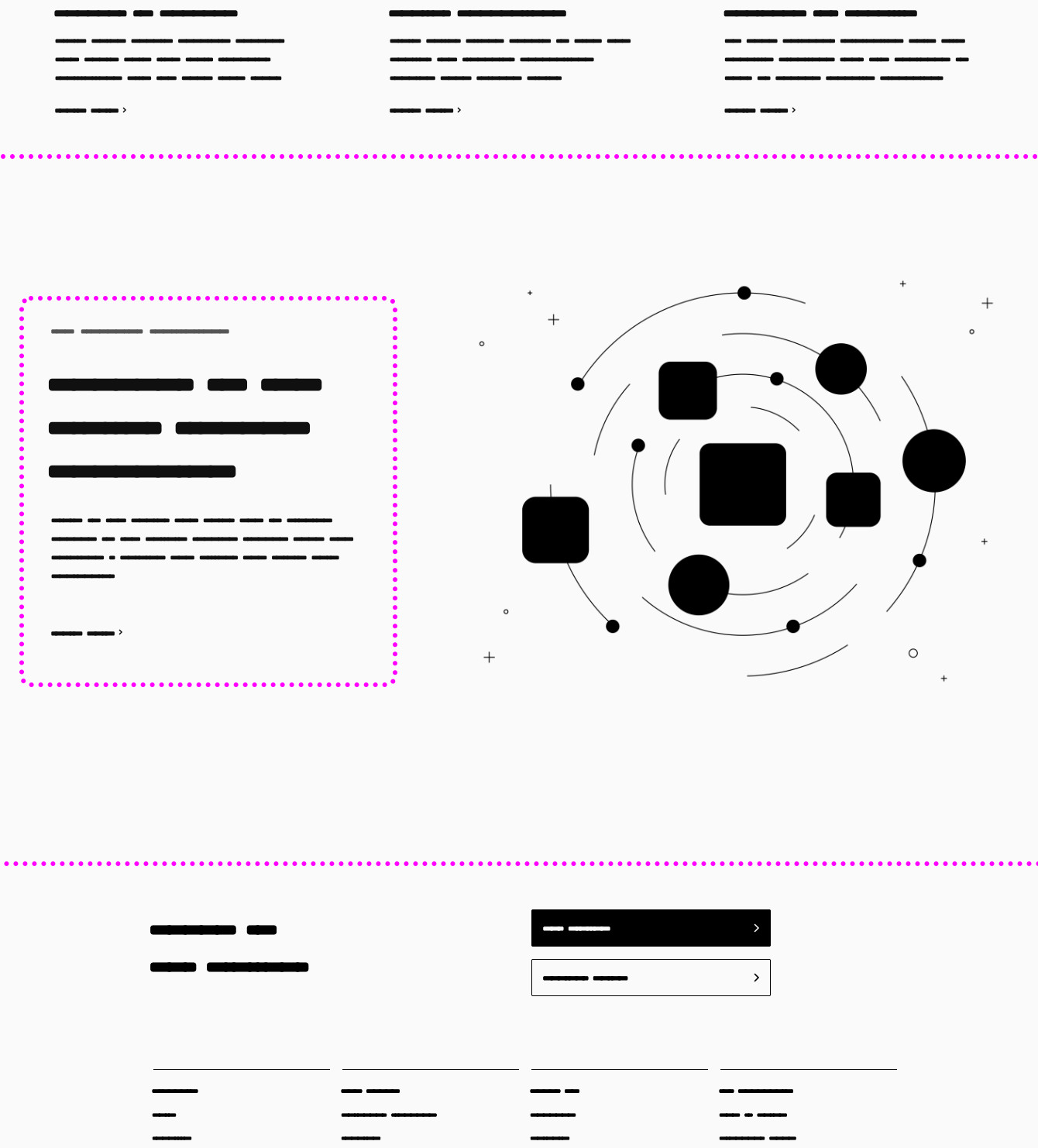

This is a low-fidelity wireframe of an interface. You might have a accurate guess of what it might represent. The more important question is how are you able to guess? There's no content clearly describing what to do, or branding to identify the product. How can we assume what this is meant for without these markers?

The answer is Jakob's Law of Familiarity.

Users prefer experiences that seem familiar. Jakob's Law of Familiarity

Wireframes represent layout; a blueprint to follow. When we choose elements for a layout, we are (hopefully) adding them with purpose, hierarchy, and user input in mind based on user's expectations learned over a period of time. We are following a blueprint whether we know it or not.

As an example, the layout of a project management tool should both be immediately identifiable and different from the layout of a social media site to be the most successful. Even when the layout does change, in the case of right-to-left languages or responsive reflow, the purpose, hierarchy and methods of user input should persist. Changing any of these creates a new experience, even if slightly.

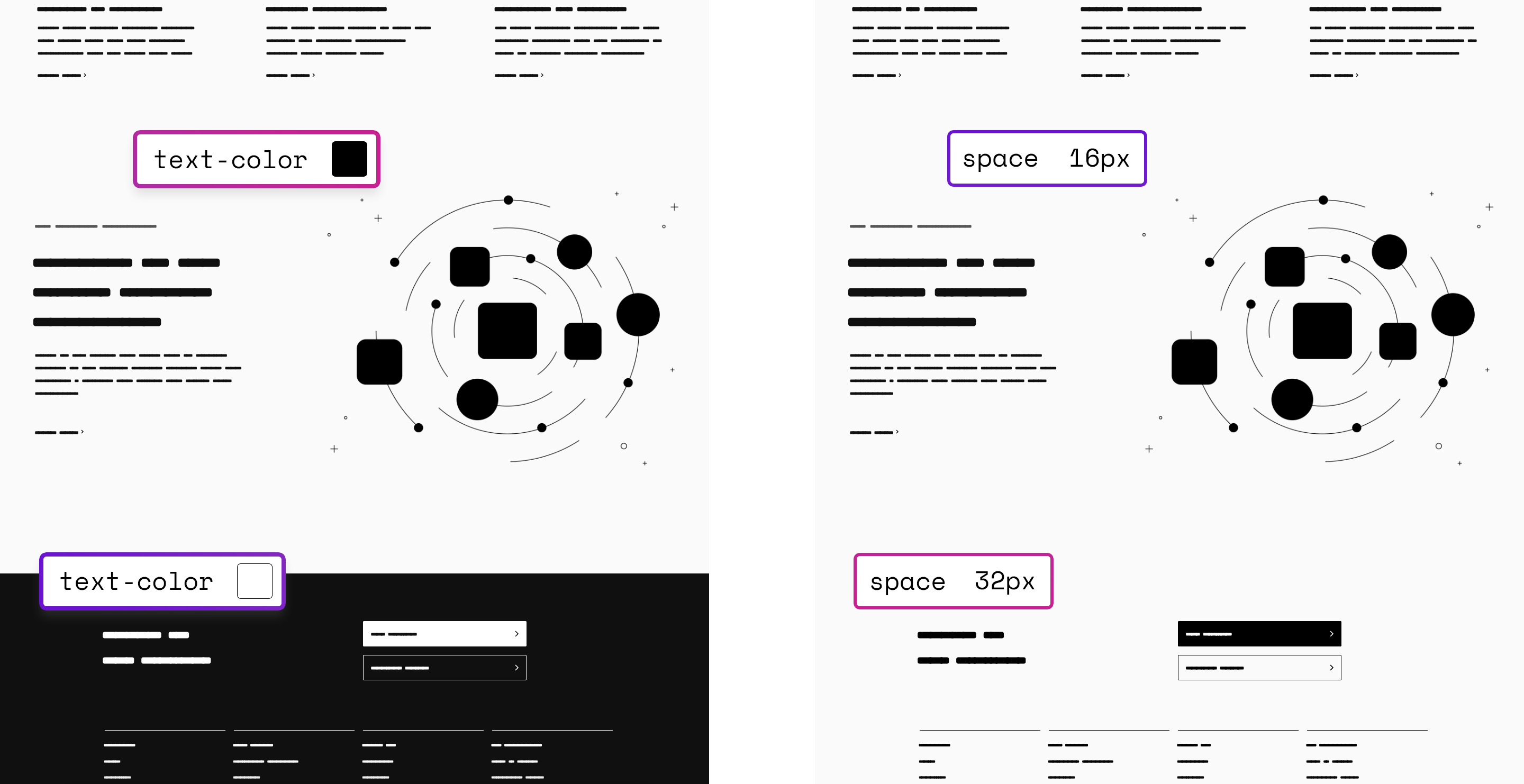

In the design system practice, we attempt to identify these user expectations and document them as reusable patterns and best practices. From here, designers can use modes to describe a change that needs to affect the entire page or (more innovately) part of the page: this area needs to be dense, this needs to standout, this needs to show another brand. A mode is a reusable expression as purposely selected values. As an example, “high contrast mode” is the collection of values curated together to convey a high contrast between content and surfaces, often meant to increase legibility.

From here, what's stopping us from putting a mode inside a mode?

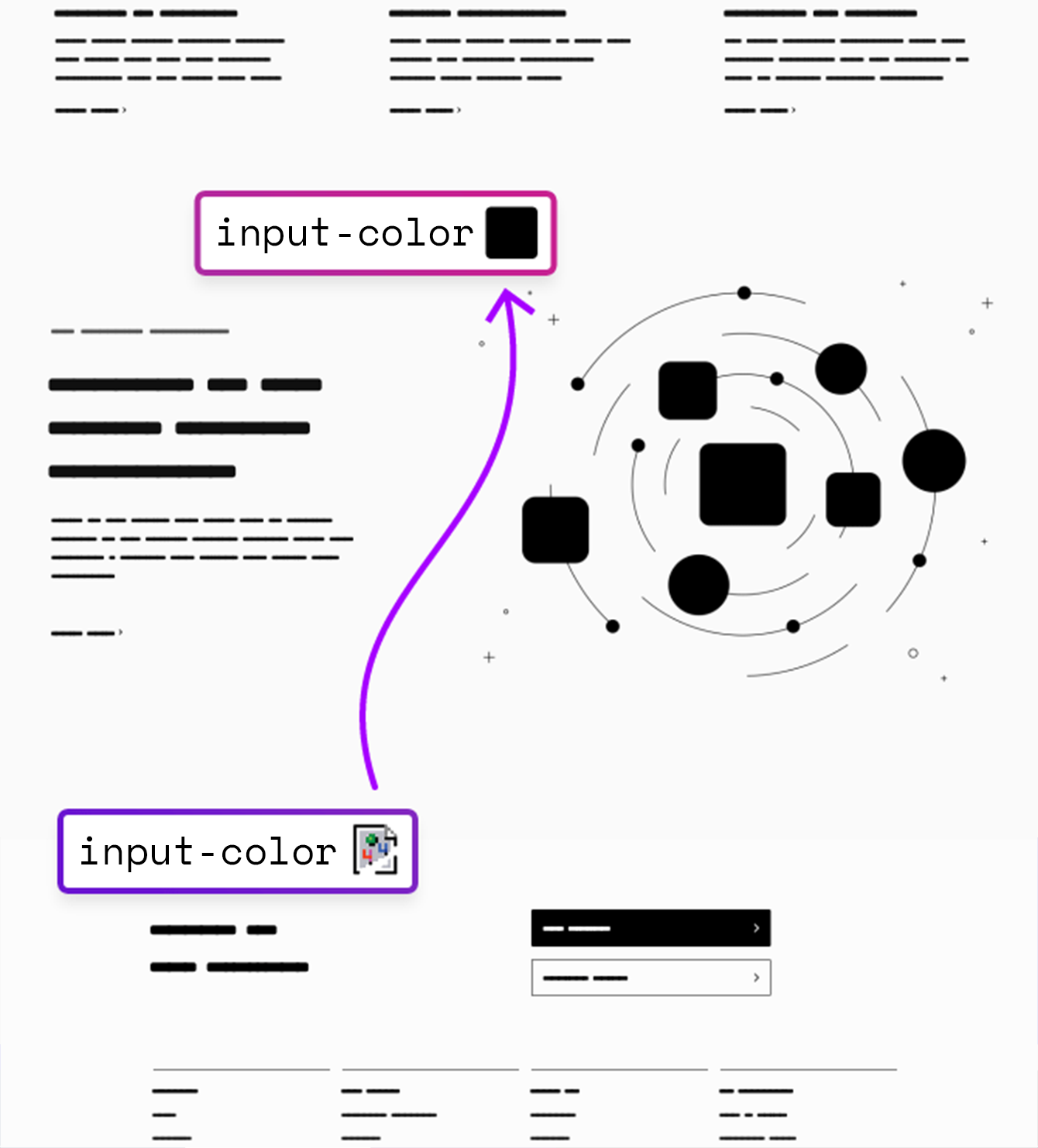

That's why I've have called this technique mise en mode, meaning “placement in mode”. It is a play on the art history term mise en abyme, which is the act of creating smaller artwork within a larger composition.

mise en mode “placement in mode”

In this idea, an experience is designed as a nested collection of modes, each with a specific purpose for being there by design.

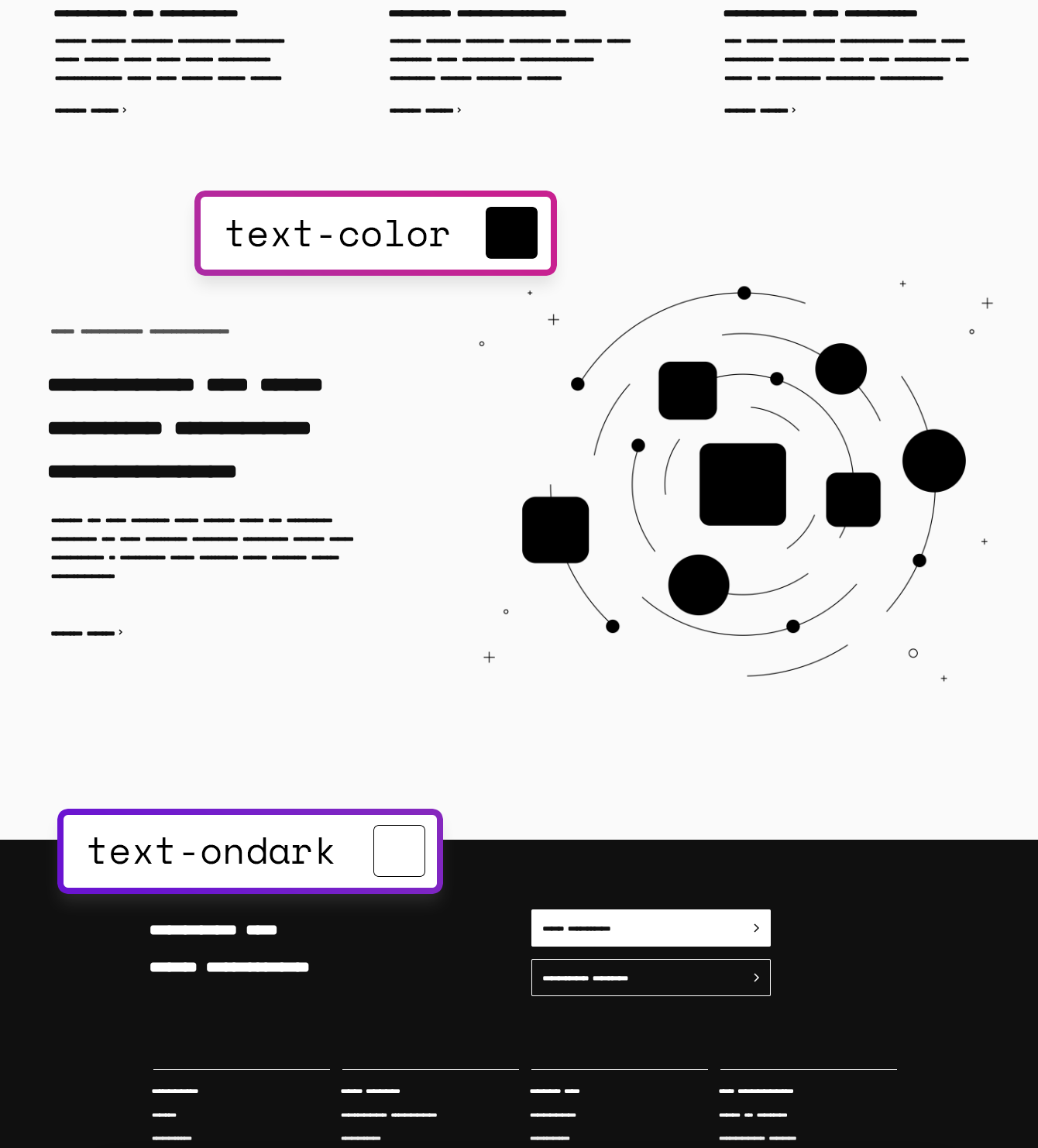

Each rectangle has the possibility of being “expressively enhanced” with new values. Each mode provides new values to existing tokens for a shared purpose. All of the tokens are curated together to express this new mode. This means that some semantics are moved from the tokens, to these new rectangular boundaries of the interface. Tokens are now simplified to naming elements and properties.

For the folks familiar with React, this is the difference between prop drilling to every component and instead reading from some useContext() provider higher in the tree.

Regardless of environment and ability you deliver a product that works Progressive enhancement, w3.org

There is no critical button,

only a button in a critical mode.

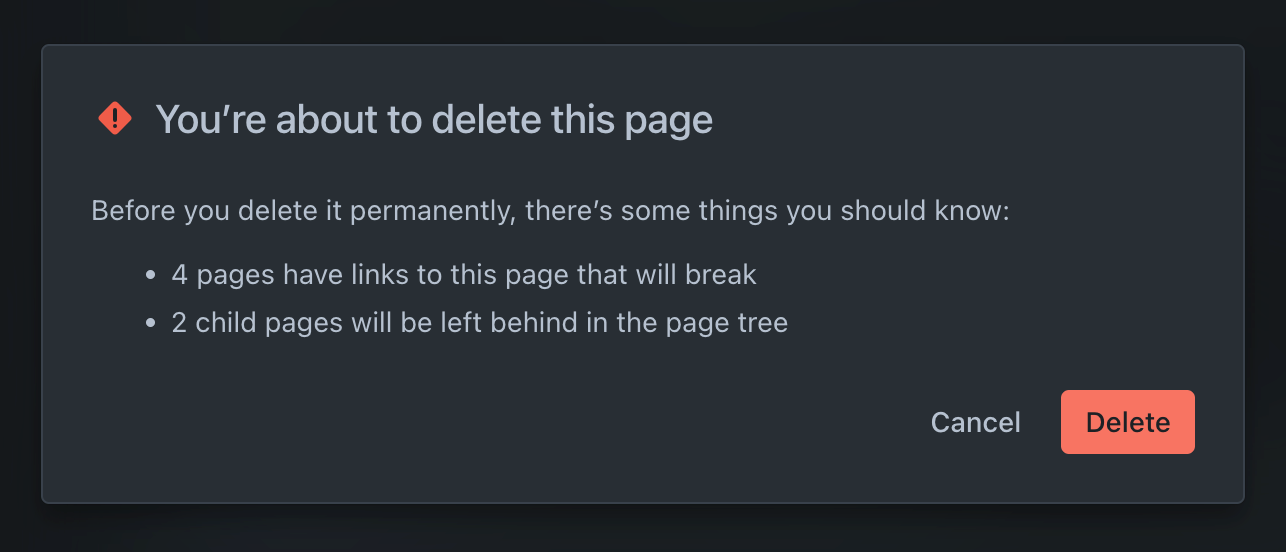

Taking this a step further, and maybe too far for some but, perhaps there is no critical button, only a button that exists within a critical mode.

While mise en mode aims to reduce the number of tokens we need to manage, it also has the possibility to reduce the number of variations that your components need to support.

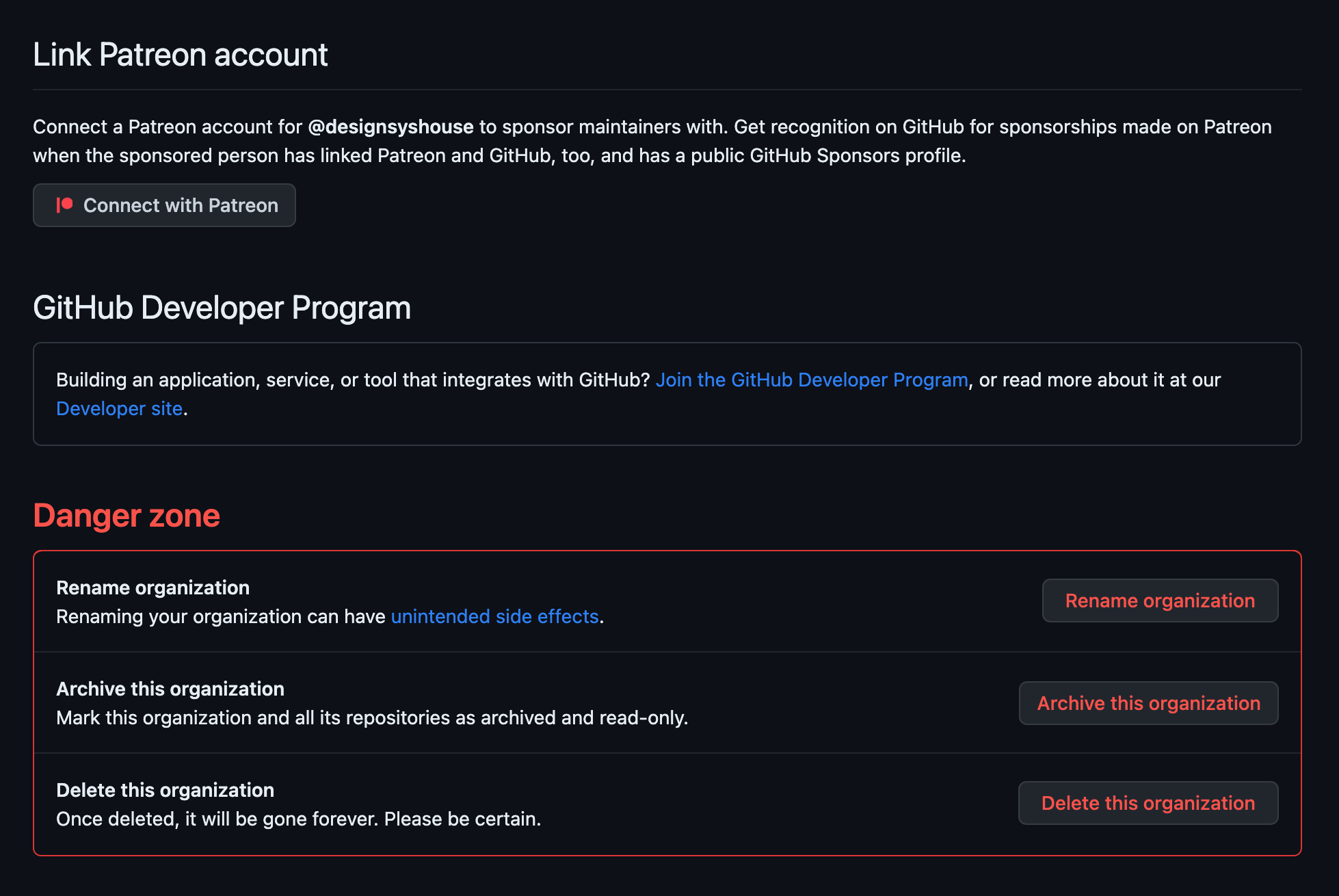

When we choose to use a critical button, we very often want to convey the idea of being dangerous to a much larger area. There is often messaging that accompanies that button to provide more context about the dangers of pressing the associated button. Therefore we could treat the entire region as critical and adjust the appearance through the scoping the token values to this boundary.

In the above example, Github profiles have a Danger Zone. While this area could have been given the same treatment as the rest of the page, the designers felt it would have more impact to convey a sense of danger. This could be done by curating a different expression through use of new color values for the properties of elements within this area. You can notice the rest of the style is otherwise identical to the larger experience. This means you can change just the values you need while defaults can support the rest. When new expressions aren't dependent on new tokens, flexibility makes this a powerful design paradigm.

Mike Mai's asks an interesting question about modes, and based on my exploration I can answer with confidence: I don't know.

What is the purpose of this treatment? Is it meant to help with reading, improve battery performance, portray a brand identity, or another user need entirely? What message is this mode meant to convey?

Asking “why?” about new designs often starts conflict because it puts designers on defense and often why designers go rogue. It's hard to articulate our needs and is just easier to avoid conflict. But maybe we could stop asking why and start saying yes!

The reason we hesitate as a system maintainer is because we will do a cost benefit analysis on this new concept. This treatment against all of the work it'll take to support it.

The conclusion would be that this would need new tokens that require new values. And those tokens need to be assigned to variants or props on components, either new or existing. Then those components need to be published as a new version of the library. And that library needs to be adopted by teams into applications.

All that work, just to change a few colors just doesn't seem worth it.

But for the folks who are asking for these changes, it is worth it. They want these rectangles to mean more. And for the design system to be a successful product, we need to support our users. We need adoption. To do this we create systems that are meant to support our users and their creative freedom of expression needs quickly.

I believe mise en mode is a powerful approach to support creativity and expression while maintaining a system to user experience design. Rounded corners, purple gradients, and flourished typography can all be applied as a mode to an underlying familiar structure. A functional layout of rectangles provide the guardrails of user expectation, while tokens provide a style-by-name interface to convey a form of expression within. Mise en mode is the practical application of form following function. So maybe to some, they're just rectangles on the internet, or maybe...

mode.place